By Elena Scotti

The Daily Beast

SPECIAL MISSIONS

11.22.14

They’ve transported dolphins, satellite parts, even wolves. Then came a call to pick up two stricken American health workers. How Phoenix became the U.S. government’s go-to rescuer.

Phoenix Air Group, a U.S.-based air charter, can fly anything.

Designed for “special missions,” the privately owned company is capable of transporting precious cargo anywhere in the world. In the 30 years since the company’s inception, “cargo” has had many meanings. For air supplier Hughes Aircraft, it was crucial satellite pieces from Russia. For Australia, oil field explosives. For an American aquarium, penguins.

This July, Phoenix got a call from a new client, this one the most serious of all. It was the U.S. Department of State. The precious cargo: two American humanitarian workers with Ebola.

For the immediate future, the thousands of American troops, hundreds of nurses and doctors bravely fighting Ebola in West Africa, Phoenix is the only quick way home. Despite more than $175 million allotted to the relief effort, the U.S. government’s rescue plan hinges on one company. Meet the most important air courier you’ve never heard of.

Phoenix Air Group, Incorporated, was launched in the rolling hills of Georgia in the late 1970s by Mark Thompson, an Atlanta native and former U.S. Army pilot. After years of flying helicopter rescue missions during the Vietnam era, Thompson decided to create his own company—this one aimed at transporting anything to safety. With just two small, double engine Beech 18s and a handful of employees, Phoenix was born.

Named for the mythological bird on his home city’s seal, Thompson’s company started small, earning a reputation as one of the few willing to transport heavy machinery by air. When the rise of foreign automakers caused an upheaval in the auto industry in the early 1980s, relocating auto parts between factories became big business. By 1984, the company had outgrown its Atlanta home, forcing Thompson to relocate to an airfield in Cartersville, Georgia, where Phoenix is based today.

Over time, the clientele began to shift and their cargo needs evolved. Unusual requests were welcomed. “Phoenix Air is not just an air charter company,” reads a bio on the company’s website. “It’s a company with a long tradition of finding solutions to client needs.” The needs were beyond Thompson’s wildest imagination. From expensive art to rigs, exotic animals to royalty, the requests kept coming. Soon the U.S. Department of Defense wanted in, contracting Phoenix to provide electronic warfare training to three of its major armed forces.

Today, with fewer than 250 employees and an estimated 35 aircraft, the company’s laid-back Southern style persists. When a client needs to move something by air, Phoenix gets it done.

Each mission is different. Sometimes the client is an international zoo, arriving with a massive dolphin tank and multiple experts to keep the animal calm during the trip to its new home. Other times it’s a country such as Kazakhstan, in need of heavy machinery. Sometimes it’s a film crew, transporting wolves to Siberia for a movie.

In 2005, the company got a call from a new, unexpected client: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC, also an Atlanta-based institute, was looking for a way to ensure that employees working in dangerous regions where they were susceptible to lethal, contagious diseases could be rescued and flown safely home.

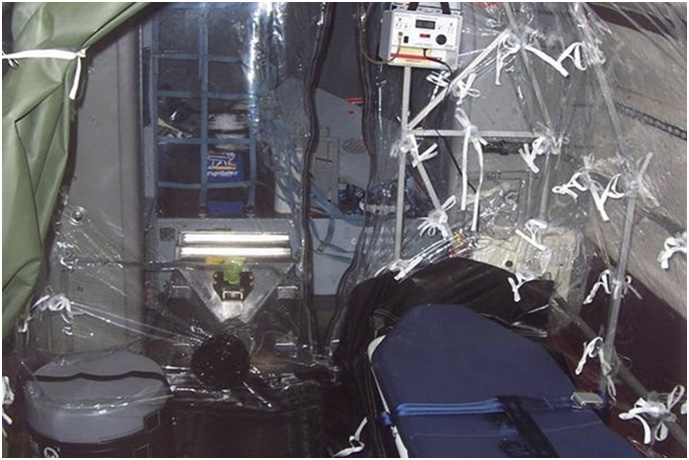

Together Phoenix and the CDC set out to solve the problem. With the help of engineers at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), the CDC created what is called an “aeromedical biocontainment system” (ABCS) made up of two large plastic tents, an interior and outer, with room for one patient. Using a HEPA-filtered ventilation system to maintain negative air pressure, the tent allows medics to employ heart and pulse monitors, as well as administer intravenous fluids. Medical professionals can enter the interior tent to check on the patient but must don personal protective equipment (PPE) to do so. Each time they exit the interior chamber, another medic must sanitize them, help them remove their PPE, and place it in a bag of materials to be burned.

Now that they had the isolation chamber, it was up to Phoenix to find a plane to carry it. The Danish Air Force, as luck would have it, had just the aircraft. Known as the Gulfstream G1159A (or Gulfstream III), the plane had an unusually massive cargo door that would allow the company to load the ABCS on and off a plane without putting the patient in danger. It was a perfect match.

With a rescue plan in place and a five-year, $4.9 million contract between Phoenix and the CDC, the planes went into storage.

In a 2007 article of Auto Pilot magazine, then-vice president and chief of operations Dent Thompson addressed apparent criticism of his company’s “on-call contract” with the CDC. “Think about a fire truck at the local fire station in your neighborhood,” Thompson told the magazine. “Fire trucks are there for emergencies, but 95% of the time they are waiting in the fire station for the emergency to occur. People might say money is being wasted to have that $150K fire truck sit idle in the station, but if it’s your house on fire, you’ll be glad that truck is here.”

This summer, the fire broke. The two American humanitarian workers infected with Ebola in Liberia were fighting for their lives. They needed to be brought home immediately.

Randall Davis, vice president, general counsel, and a pilot for Phoenix who bills himself as the “flying lawyer,” remembers the day well. “It was late July. We got a call from the State Department, someone who works on repatriation of Americans who are ill,” he says. “They said, ‘We’ve been talking to the CDC and we understand you’ve got these isolation chambers. Could you do it for Ebola?’”

In the months before the Ebola epidemic, Davis and his team were spending a great deal of time on a war readiness program with the DOD and NATO. For this “electronic warfare,” Phoenix was tasked with flying a sophisticated plane, hidden from radar, over something such as a Navy ship—to prepare for the real thing. “We get paid to be a state-of-the-art bad guy,” says Davis. “It’s like war games.”

This time, the battle was real.

While the Gulfstream III and ABCS, both specifically designated as an air ambulance, had yet to be used, the staff at Phoenix was experienced in transporting patients via air ambulance, both domestic and international. Davis and his team knew it wouldn’t be easy, but they were ready. After weeks of training, the first mission set out to retrieve Kent Brantly, an American doctor.

Two days after Brantly’s evacuation to Atlanta, another team set out to transport nurse Nancy Writebol. This time, Davis was in the cockpit. Just 30 feet from the chamber in which Writebol lay for the 16-hour flight, he could make out no more than a “form” through the plastic sheeting surrounding her tent. But the nurse, EMT, and doctor inside, he says, were heroic: “I can’t give them enough credit. They are wonderful human beings. If you were stuck in a foreign country, you would love to have this group come and get you.”

Writebol’s flight would turn out to be a success, as have nearly all of the 15 Ebola missions that Phoenix has performed thus far, with destinations ranging from Switzerland to France. Davis was also a part of the mission to transport the first person to be infected with Ebola in the United States, Nina Pham, from Dallas to a facility in Maryland. He was not with the Sierra Leonean doctor who was flown to Nebraska on Saturday—the first of the 15 not to survive.

Despite intimate, long flights with Ebola patients, many of whom are very sick, no one at Phoenix has contracted the disease. “It shows if you know what you’re doing, it can be done properly,” Davis says.

As of now, Phoenix hold the keys to the only aircraft on the planet capable of ensuring 100 percent safety for those wishing to transport an Ebola victim out of West Africa. “We are it,” Davis says when I ask if the military has a plan for how to get an infected American service member out of Liberia. While Davis and others at Phoenix weren’t expecting to get that first call for Brantly (“It came out of nowhere”), they were prepared for it. “We can do this efficiently and we can do a good job,” he says.

In Davis’s mind, it’s the medical workers, not Phoenix, who deserve attention. “It’s nice to be able to help out in such a direct manner, but all we have to do is fly the plane,” he says. The heroic individuals Phoenix carries home and the ones who sit at their bedside during the flight play the most important role of all. “These medical workers are amazing, such selfless people,” he says. “It’s about saving lives—and that’s what it should be about.”

See full article here