As Georgia Airfield Welcomes Back ‘Ebola Gray,’ State Department Plans Expanded Program

By Cameron McWhirter and Betsy McKay

The Wall Street Journal

CARTERSVILLE, Ga.—In a nondescript hangar at a small airfield here, a shiny gray jet was serviced Friday after delivering an Ebola patient from West Africa to a hospital near Washington, D.C.

The modified Gulfstream G-III—dubbed by some “the Ebola Gray”—is one of three planes that aircraft-charter company Phoenix Air Group Inc. has used since August for about 35 Ebola-related flights from West Africa to the U.S., Germany and elsewhere.

The planes are almost the only lifeline from West Africa for foreign organizations trying to ensure their staffs receive Western-level medical care if they contract Ebola. “Right now, we continue to be the company that the world turns to,” said Dent Thompson, vice president and chief operations officer of Georgia-based Phoenix Air, who has been coordinating the Ebola flights.

But with a number of infectious-disease outbreaks in the world today, Phoenix Air is scarcely enough. Each plane carries only one passenger and has to undergo a 24-hour decontamination process before it can be used again.

“Phoenix can move one patient at a time, and it takes three days,” said William Walters, director of operational medicine at the State Department, which has brokered medical evacuations for Ebola patients to multiple countries.

The Ebola epidemic may have ebbed, with Liberia’s last patient discharged earlier this month. But it is far from over: Cases are still rising in Sierra Leone and Guinea.

On Friday, Phoenix Air delivered an American health-care worker who contracted Ebola in Sierra Leone to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., for treatment. The Phoenix Air plane landed in Washington around 4 a.m., and shortly thereafter the jet was in Cartersville, set to be decontaminated and readied for another flight, Mr. Thompson said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced Friday that other Americans who may have been recently exposed to Ebola but haven’t tested positive were going to be flown out of West Africa. One person was being flown to Atlanta, to be near Emory University Hospital, which has treated other Ebola patients, according to the CDC.

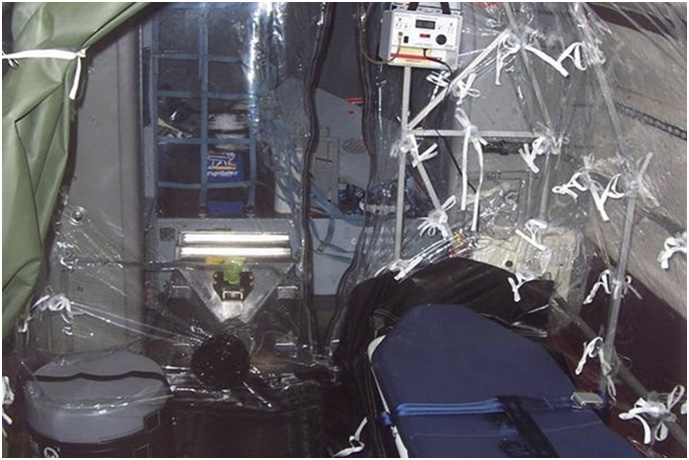

The Aeromedical Biological Containment System is a portable, tent-like device installed in a modified Gulfstream G-III aircraft, providing a means of emergency transport of exposed or contagious personnel from the field. PHOTO: REUTERS

The State Department is working on expanding medical-evacuation capabilities. With a $5 million grant from philanthropist and entrepreneur Paul Allen, it is overseeing the construction and testing of two biocontainment units that are large enough for four patients each, along with a medical crew, and can be loaded onto a 747-400 or similar jumbo jet and then unloaded with any patients, without requiring decontamination of the whole plane.

Dr. Walters said the new biocontainment units won’t be ready until May, assuming they prove worthy in testing. The new medevac units “will represent the next generation in biocontainment capability, for the current outbreak and those that may follow,” he said.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Air Force announced it had developed three “transport isolation systems” for its planes to handle patients with Ebola or other highly infectious diseases, but it hasn’t yet tried the systems with any patients, according to an Air Force spokeswoman.

Mr. Allen decided to fund the expansion of medical evacuation to help aid organizations attract foreign staff to West Africa, said Gabrielle Fitzgerald, director of the Ebola program. “This was seen as a way to incentivize people to know that if they got there and got sick, there would be a way to get home,” she said. Mr. Allen also set aside $2.5 million to help patients cover the cost of evacuations beyond what their insurance will cover. So far, $1.25 million of that money has been spent for nine patient evacuations, said Ms. Fitzgerald. Mr. Allen has also given money to the World Health Organization to help coordinate global coordination of medical evacuations.

For the time being, though, the responsibility of evacuating patients rests with closely held Phoenix Air, which has a contract for medical evacuations with the State Department. It also has contracts with the U.S. to haul explosives, play the enemy in military war-game exercises and transport criminals for various federal law-enforcement agencies. It shuttled the U.S. presidential delegation to and from Sochi during the 2014 Winter Olympics.

In 2008, Phoenix Air, the CDC and the Defense Department began developing an “Aeromedical Biological Containment System,” or ABCS, for airplanes to transport patients with highly infectious diseases.

The system—a self-contained, two-compartment tent of clear plastic, tubing, zippered doors and medical equipment—is placed in the back half of the modified Gulfstream. Funding for the project lapsed in 2010 due to federal budget cuts, according to Phoenix Air. “We just put everything on a shelf because we knew eventually there would be an epidemic,” Mr. Thompson said.

In late July, when two American missionaries in Liberia contracted Ebola, the State Department called Phoenix Air to pull the biocontainment system off the shelf. “It was scary to start with,” said Michael Flueckiger, medical director of Phoenix’s air ambulance division. “We didn’t know: Could we do this safely?”

Mr. Thompson said the cost per flight varies depending on fuel, distance, time and other factors. The airline was paid $200,000 apiece to fly missionaries Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol from Liberia to Atlanta in August.

Since then, Phoenix Air jets have been on call for Ebola flights any time of day or night. Emergency requests for flights have come in as late 2 a.m. “We sit here on what we call hot standby 24-7,” said Mr. Thompson.

Dr. Flueckiger said “anti-scientific hysteria” over Ebola has complicated the job. Many governments have refused to allow airplanes with Ebola patients to land and refuel. At one foreign airport, which Mr. Thompson wouldn’t name, armed police drew their weapons when they thought the pilots might try to leave the tarmac, he said.

The U.S. requires that Phoenix Air land at one of five airports designated for travelers from the three main Ebola-afflicted countries—a rule that has at times required an extra stop with critically ill patients.

Some Phoenix Air medical crew members with jobs at other medical facilities were advised not to go on trips to fetch Ebola patients, because they wouldn’t be able to return to their main jobs for 21 days after the flight, Dr. Flueckiger said.

In the early days of the outbreak, the company was “getting squeezed to death in terms of our staffing,” he said.

Since then, Phoenix Air has hired more medical staff fulltime to avoid conflict with hospitals and others worried about the disease, Mr. Thompson said.

“Ebola evokes an irrational fear in people, even medical people,” he said.